The brain of man and his adaptation to fatherhood

Traditionally, the raising and care of children has been one of those areas associated with the feminine : in this case, more specifically, with the role of the mother. The realm of the maternal seems to encompass everything that is relevant to us during the first months of our life. A mother provides warmth, food, affection and the first contact with language (even before she was born, her voice is audible from the uterus).

Going a little further, we could hold, as suggested by the French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan , that the look that a mother directs towards us is in itself the mirror before which we forge a very primitive idea of our own "I". In this sense, the germ of what will one day be our identity is thrown at us by a loved one.

Male fatherhood

While it is not uncommon for psychoanalysts like Lacan to emphasize the figure of the mother, it is surprising to see to what extent the conception of the maternal as something sacred is rooted in the depths of our culture . And yet, the adult males of our species are perfectly capable of raising and educating their offspring (and even adopted children). This is also true in cases in which the traditional nuclear family model is not given, with father, mother and offspring.

Also, it's been a long time since we realized that the human being is a unique case of paternal care among all forms of life . This is so, basically, because in most of the animals in which sexual reproduction occurs, the role of the father is quite discreet. Let's see it

Evolutionary rarity

First, the normal thing in vertebrates is that the reproductive role of the male is limited to the search for a mate and copulation. Obviously, this means that the moment of "being a father" and the birth of the offspring takes place in two distinct phases. By the time the poor pups have arrived in the world, the male progenitor is far away, both in time and space. The role of the "father who will buy tobacco" is perfectly normalized in the genetics of the animal kingdom .

Second, because, if we turn our gaze towards other branches of the evolutionary tree in which we are included, we will have many chances to see the following scheme applied:

1. One strongly cohesive couple formed by the female and the young .

2. A father figure, whose role is quite secondary , responsible for making the relationship maintained in the female-breeding dyad can last long enough to raise an adult organism with full capabilities.

In those cases in which the male is actively concerned about the safety of their offspring, their role is usually limited to that, trying to ensure the survival of their own against any threat. It could be said, for example, that for a great dorsican gorilla to be a father means to try to squeeze anything that could disturb his offspring.

As a result of this, there are very few species in which the functions between males and females in regard to the care of the offspring are close to symmetry . Only in birds and in some mammals in which the degree of sexual dimorphism * is low is low, the parent-child bond will be strong ... and this happens very rarely. In addition, at least in other animals, a strong parental role is synonymous with monogamy **.

The curious thing about this is that these conditions are rare even in animals as social as the apes. The non-extinct relatives closest to us evolutionarily whose males care for the offspring are the gibbons and the siamang, and both are primates that do not even belong to the family of hominids, to which the Homo sapiens. Our closest living relatives, the chimpanzees and the bonobos They are not monogamous and relations between males and their offspring are weak. The case of humans, moreover, is special, because it seems that we tend towards monogamy only partially: our own may be social monogamy, but not sexual monogamy.

Breaking the paradigm

Be that as it may, in the modern human being we find a species that presents little sexual dimorphism and a tendency, at least statistically, toward social monogamy. This means that participation in the care of children is similar in fathers and mothers (although it is very questionable that this involvement by both parties is equal or symmetric).

That being the case, it is possible that whoever reads these lines is asking himself in what exactly is the attachment that men feel for their children and everything related to their parental behavior (or, in other words, the "paternal instinct"). We have seen that, most likely, social monogamy is an option that has recently taken place in our chain of hominid ancestors.It has also been pointed out how rare is the genuinely paternal role in the evolutionary tree, even among the species most similar to ours. Therefore, it would be reasonable to think that, biologically and psychologically, women are much better prepared to raise children, and that parenting is a circumstantial imposition to which men have no choice but to adjust, a "botched" "Last minute in the evolution of our species.

To what extent is the paternal care of offspring central to the behavior of men?Is everyone's brain ready? Homo sapiens to conform to the role of father?

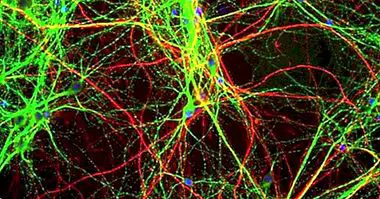

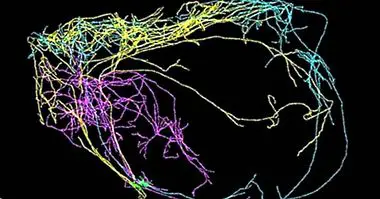

While establishing a comparison between the adequacy of male and female psychology for the role of father or mother would lead to an eternal debate, there is scientific evidence to support that, at least in part, paternity changes the structure of the brain of men , something that also happens to women with motherhood . During the first months of postpartum the gray matter present in areas of the brain of man important in the processing of social information (lateral prefrontal cortex) and parental motivation (hypothalamus, striatum and amygdala) increases. At the same time, brain reconfiguration affects other areas of the brain, this time reducing its volume of gray matter. This occurs in the orbitofrontal cortex, the insula, and the posterior cingulate cortex. That is to say: the repertoire of new behaviors that entails being a father is matched by a repertoire of physical changes in the brain.

All this leads us to think that, for more or less genetic reasons, more or less social, the adjustment of man's behavior to his new role as caretaker is strongly based on the biology of his own brain. This explains why, as a general rule, all humans can adapt to the new responsibilities that come with having a son or daughter.

Moral dyes

Now, it could be said that the question of whether the interest shown before children has the same nature in men and women is colored by a moral, emotional or even visceral component . The apparently aseptic question "can paternity be comparable to motherhood?" Becomes "do men have the same capacity to give themselves to a pure and noble love for children, as clearly happens in women?" question, although perfectly legitimate, is difficult to answer.

We know that reality is something very complex and that it can never be covered by each of the investigations that are carried out daily. In a certain sense, translating a topic that generates personal interest into a hypothesis that can be addressed by the scientific method entails leaving elements of reality outside the research ***. We also know that, since reality is so complicated, within the theoretical body provided by science there are always remnants of uncertainty from which it is possible to rethink the conclusions of an investigation . In that sense, the scientific method is at the same time a way of generating knowledge and a tool to systematically test what seems obvious to us. For the case that concerns us this means that, for now, the honor of the paternal role can be safe before common sense ...

However, someone might suggest, for example, that the interest in the offspring shown by the males of some species (and its corresponding neuroanatomical adaptation) is only a strategy to closely monitor offspring and the female with whom they have procreated. , even becoming self-deceived about the nature of their feelings; all to ensure its own genetic continuity over time. It should be noted, however, that the core of this problem is not only a matter of differences between sexes, but depends on our way of understanding the interaction between genetics and our affective relationships . Feeling attachment for offspring for purely biological reasons is something females could also be suspicious of.

Some people think, not without reason, that intense and too continuous scientific speculation can be discouraging. Fortunately, along with purely scientific thinking, we are accompanied by the certainty that our own feelings and subjective states of consciousness are genuine in themselves. It would be a pity if a conception of radically physicalistic human psychology ruined a parent-child experience.

Author's notes:

* Differences in appearance and size between male and female

** There is, however, a very curious case in which the male takes care of offspring apart from the female. In the fish of the syngnathid family, to which, for example, seahorses belong, the males are responsible for incubating the eggs in a cavity of their body. After the hatching of the eggs, the male expels the young through a series of seizure-like movements and then disregards them ... or, at least, those that have not been eaten by then.In summary, it is not a particularly endearing case and it is better not to draw parallels between this and what happens in humans.

*** In philosophy of science, this dilemma is approached from a position called reductionism and from the philosophical approaches opposed to it.