How human memory works (and how it deceives us)

Many people believe that memory is a kind of storage where we store our memories . Others, more friends of technology, understand that memory is more like a computer in whose hard drive we are filing our learning, experiences and life experiences, so that we can use them when we need them.

But the truth is that both conceptions are wrong.

- Related article: "Types of memory"

So, how does human memory work?

We do not have any memory as such stored in our brain. That would be, from a physical and biological point of view, literally impossible.

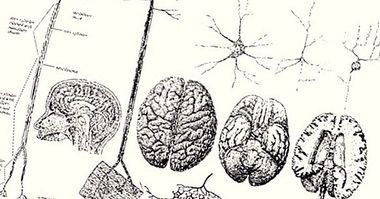

What the brain consolidates in memory are "patterns of functioning ", That is, the way in which specific groups of neurons are activated every time we learn something new.

I do not want to make a big mess of this, so I will just say that all information that enters the brain becomes a chemical electrical stimulus.

Neuroscience of memories

What the brain keeps is the frequency, amplitude and particular sequence of neural circuits involved in learning. A specific fact is not stored, but the way in which the system works with that specific fact .

Then, when we remember something consciously or without our intending it, an image comes to mind, what our brain does is reissue that specific functioning pattern again. And this has serious implications. Perhaps the most important is that our memory deceives us .

We do not recover the memory as it was stored, but rather we put it back together whenever we need it from the reactivation of the corresponding operating patterns.

The "defects" of memory

The problem is that this evocation mechanism is en bloc. The commissioning of the system can bring as stowaways to other memories that have been filtered , that belong to another time or another place.

Science and interference

I'm going to tell you an experiment that shows how vulnerable we are to memory interference, and how we can be subtly induced to remember something in the wrong way, or that just never happened.

A group of people was shown a video in which a traffic accident could be observed, specifically the collision between two vehicles. Then, they were divided into two smaller groups and interrogated, separately, about what they had seen. The members of the first group were asked to estimate approximately how fast the cars were moving when they "collided".

The same group was asked for the members of the second group, but with a seemingly insignificant difference. They were asked at what speed they estimated the cars were moving when one was "embedded" in the other.

The members of the last group, on average, calculated values much higher than those of the first group, where the cars had simply "crashed". Some time later, they were met again in the laboratory and asked for details about the video accident.

The double of the members of the group in which the cars had been "embedded" in relation to the members of the other group They said they saw windshield windows exploded and scattered on the sidewalk . It should be noted that no windshield had been broken in the video in question.

We remember with difficulty

We believe that we can remember the past with precision, but it is not so . The brain is forced to reconstruct the memory every time we decide to recover it; it must be assembled as if it were a puzzle that, to top it all, does not have all the pieces, since much of the information is not available because it was never stored or filtered by the attention systems.

When we remember a certain episode of our life, such as the day we leave the university, or when we get our first job, the recovery of the memory does not take place in a clean and intact way, as when, for example, we open a text document on our computer, but that the brain must make an active effort to track information that is scattered, and then, gather all those diverse elements and fragmented to present us with a version as solid and elegant as possible of what happened.

The brain is responsible for "filling" the voids of memory

Potholes and blank spaces are filled into the brain by scraps of other memories, personal conjectures and abundant pre-established beliefs, with the ultimate goal of obtaining a more or less coherent whole that meets our expectations.

This happens basically for three reasons:

As we said before, when we live a certain event, what the brain keeps is a functioning pattern. In the process, much of the original information never gets into the memory. And if it enters, it does not consolidate in memory effectively. That forms bumps in the process that take away congruence from the story when we want to remember it.

Then we have the problem of false and unrelated memories that mix with the real memory when we bring it to consciousness. Here something similar happens when we throw a net to the sea, we can catch some small fish, which is what interests us, but many times we also find garbage that was once thrown into the ocean: An old shoe, a plastic bag, a bottle empty soda, etc.

This phenomenon occurs because the brain is permanently receiving new information , consolidating learning for which many times it resorts to the same neural circuits that are being used for other learning, which can cause some interference.

Thus, the experience that one wishes to archive in memory can be merged or modified with previous experiences, causing them to end up being stored as an undifferentiated whole.

Giving meaning and logic to the world around us

By last, the brain is an organ interested in giving meaning to the world . In fact, it even seems that he feels an abhorrent hatred for uncertainty and inconsistencies.

And it is in his eagerness to explain everything when, when he ignores certain data in particular, he invents them to get by and thus save appearances. We have another fissure here in the system, dear reader. The essence of memory is not reproductive, but reconstructive , and as such, vulnerable to multiple forms of interference.